“Well, we are quite in your hands, Mr. Holmes,” said old Cunningham. “Anything which you or the inspector may suggest will most certainly be done.”

“In the first place,” said Holmes, “I should like you to offer a reward — coming from yourself, for the officials may take a little time before they would agree upon the sum, and these things cannot be done too promptly. I have jotted down the form here, if you would not mind signing it. Fifty pounds was quite enough, I thought.”

“I would willingly give five hundred,” said the J. P., taking the slip of paper and the pencil which Holmes handed to him. “This is not quite correct, however,” he added, glancing over the document.

“I wrote it rather hurriedly.”

“You see you begin, ‘Whereas, at about a quarter to one on Tuesday morning an attempt was made,’ and so on. It was at a quarter to twelve, as a matter of fact.”

I was pained at the mistake, for I knew how keenly Holmes would feel any slip of the kind. It was his specialty to be accurate as to fact, but his recent illness had shaken him, and this one little incident was enough to show me that he was still far from being himself. He was obviously embarrassed for an instant, while the inspector raised his eyebrows, and Alec Cunningham burst into a laugh. The old gentleman corrected the mistake, however, and handed the paper back to Holmes.

“Get it printed as soon as possible,” he said; “I think your idea is an excellent one.”

Holmes put the slip of paper carefully away into his pocketbook.

“And now,” said he, “it really would be a good thing that we should all go over the house together and make certain that this rather erratic burglar did not, after all, carry anything away with him.”

Before entering, Holmes made an examination of the door which had been forced. It was evident that a chisel or strong knife had been thrust in, and the lock forced back with it. We could see the marks in the wood where it had been pushed in.

“You don’t use bars, then?” he asked.

“We have never found it necessary.”

“You don’t keep a dog?”

“Yes, but he is chained on the other side of the house.”

“When do the servants go to bed?”

“About ten.”

“I understand that William was usually in bed also at that hour?”

“Yes.”

“It is singular that on this particular night he should have been up. Now, I should be very glad if you would have the kindness to show us over the house, Mr. Cunningham.”

A stone-flagged passage, with the kitchens branching away from it, led by a wooden staircase directly to the first floor of the house. It came out upon the landing opposite to a second more ornamental stair which came up from the front hall. Out of this landing opened the drawing-room and several bedrooms, including those of Mr. Cunningham and his son. Holmes walked slowly, taking keen note of the architecture of the house. I could tell from his expression that he was on a hot scent, and yet I could not in the least imagine in what direction his inferences were leading him.

“My good sir,” said Mr. Cunningharn, with some impatience, “this is surely very unnecessary. That is my room at the end of the stairs, and my son’s is the one beyond it. I leave it to your judgment whether it was possible for the thief to have come up here without disturbing us.”

“You must try round and get on a fresh scent, I fancy,” said the son with a rather malicious smile.

“Still, I must ask you to humour me a little further. I should like, for example, to see how far the windows of the bedrooms command the front. This, I understand, is your son’s room” — he pushed open the door — “and that, I presume is the dressing room in which he sat smoking when the alarm was given. Where does the window of that look out to?” He stepped across the bedroom, pushed open the door, and glanced round the other chamber.

“I hope that you are satisfied now?” said Mr. Cunningham tartly.

“Thank you, I think I have seen all that I wished.”

“Then if it is really necessary we can go into my room.”

“If it is not too much trouble.”

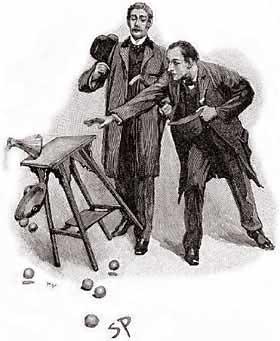

The J. P. shrugged his shoulders and led the way into his own chamber, which was a plainly furnished and commonplace room. As we moved across it in the direction of the window, Holmes fell back until he and I were the last of the group. Near the foot of the bed stood a dish of oranges and a carafe of water. As we passed it Holmes, to my unutterable astonishment, leaned over in front of me and deliberately knocked the whole thing over. The glass smashed into a thousand pieces and the fruit rolled about into every corner of the room.

The J. P. shrugged his shoulders and led the way into his own chamber, which was a plainly furnished and commonplace room. As we moved across it in the direction of the window, Holmes fell back until he and I were the last of the group. Near the foot of the bed stood a dish of oranges and a carafe of water. As we passed it Holmes, to my unutterable astonishment, leaned over in front of me and deliberately knocked the whole thing over. The glass smashed into a thousand pieces and the fruit rolled about into every corner of the room.

“You’ve done it now, Watson,” said he coolly. “A pretty mess you’ve made of the carpet.”

I stooped in some confusion and began to pick up the fruit, understanding for some reason my companion desired me to take the blame upon myself. The others did the same and set the table on its legs again.

“Hullo!” cried the inspector, “where’s he got to?”

Holmes had disappeared.

“Wait here an instant,” said young Alec Cunningham. “The fellow is off his head, in my opinion. Come with me, father, and see where he has got to!”

They rushed out of the room, leaving the inspector, the colonel, and me staring at each other.

” ‘Pon my word, I am inclined to agree with Master Alec,” said the official. “It may be the effect of this illness, but it seems to me that –”

His words were cut short by a sudden scream of “Help! Help! Murder!” With a thrill I recognized the voice as that of my friend. I rushed madly from the room on to the landing. The cries which had sunk down into a hoarse, inarticulate shouting, came from the room which we had first visited. I dashed in, and on into the dressing-room beyond. The two Cunninghams were bending over the prostrate figure of Sherlock Holmes, the younger clutching his throat with both hands, while the elder seemed to be twisting one of his wrists. In an instant the three of us had torn them away from him, and Holmes staggered to his feet, very pale and evidently greatly exhausted.

“Arrest these men, Inspector,” he gasped.

“On what charge?”

“That of murdering their coachman, William Kirwan.”

The inspector stared about him in bewilderment. “Oh, come now, Mr. Holmes,” said he at last, “I’m sure you don’t really mean to –”

“Tut, man, look at their faces!” cried Holmes curtly.

Never certainly have I seen a plainer confession of guilt upon human countenances. The older man seemed numbed and dazed, with a heavy, sullen expression upon his strongly marked face. The son, on the other hand, had dropped all that jaunty, dashing style which had characterized him, and the ferocity of a dangerous wild beast gleamed in his dark eyes and distorted his handsome features. The inspector said nothing, but, stepping to the door, he blew his whistle. Two of his constables came at the call.

“I have no alternative, Mr. Cunningham,” said he. “I trust that this may all prove to be an absurd mistake, but you can see that Ah, would you? Drop it!” He struck out with his hand, and a revolver which the younger man was in the act of cocking clattered down upon the floor.

“Keep that,” said Holmes, quietly putting his foot upon it; “you will find it useful at the trial. But this is what we really wanted.” He held up a little crumpled piece of paper.

“The remainder of the sheet!” cried the inspector.

“Precisely.”

“And where was it?”

“Where I was sure it must be. I’ll make the whole matter clear to you presently. I think, Colonel, that you and Watson might return now, and I will be with you again in an hour at the furthest. The inspector and I must have a word with the prisoners, but you will certainly see me back at luncheon time.”

Sherlock Holmes was as good as his word, for about one o’clock he rejoined us in the colonel’s smoking-room. He was accompanied by a little elderly gentleman, who was introduced to me as the Mr. Acton whose house had been the scene of the original burglary.