“There being no fear of interruption I proceeded to burgle the house. Burglary has always been an alternative profession had I cared to adopt it, and I have little doubt that I should have come to the front. Observe what I found. You see the gas-pipe along the skirting here. Very good. It rises in the angle of the wall, and there is a tap here in the corner. The pipe runs out into the strong-room, as you can see, and ends in that plaster rose in the centre of the ceiling, where it is concealed by the ornamentation. That end is wide open. At any moment by turning the outside tap the room could be flooded with gas. With door and shutter closed and the tap full on I would not give two minutes of conscious sensation to anyone shut up in that little chamber. By what devilish device he decoyed them there I do not know, but once inside the door they were at his mercy.”

The inspector examined the pipe with interest. “One of our officers mentioned the smell of gas,” said he, “but of course the window and door were open then, and the paint–or some of it–was already about. He had begun the work of painting the day before, according to his story. But what next, Mr. Holmes?”

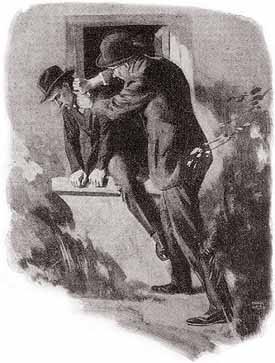

“Well, then came an incident which was rather unexpected to myself. I was slipping through the pantry window in the early dawn when I felt a hand inside my collar, and a voice said: ‘Now, you rascal, what are you doing in there?’ When I could twist my head round I looked into the tinted spectacles of my friend and rival, Mr. Barker. It was a curious foregathering and set us both smiling. It seems that he had been engaged by Dr. Ray Ernest’s family to make some investigations and had come to the same conclusion as to foul play. He had watched the house for some days and had spotted Dr. Watson as one of the obviously suspicious characters who had called there. He could hardly arrest Watson, but when he saw a man actually climbing out of the pantry window there came a limit to his restraint. Of course, I told him how matters stood and we continued the case together.”

“Why him? Why not us?”

“Because it was in my mind to put that little test which answered so admirably. I fear you would not have gone so far.”

The inspector smiled.

“Well, maybe not. I understand that I have your word, Mr. Holmes, that you step right out of the case now and that you turn all your results over to us.”

“Certainly, that is always my custom.”

“Well, in the name of the force I thank you. It seems a clear case, as you put it, and there can’t be much difficulty over the bodies.”

“I’ll show you a grim little bit of evidence,” said Holmes, “and I am sure Amberley himself never observed it. You’ll get results, Inspector, by always putting yourself in the other fellow’s place, and thinking what you would do yourself. It takes some imagination, but it pays. Now, we will suppose that you were shut up in this little room, had not two minutes to live, but wanted to get even with the fiend who was probably mocking at you from the other side of the door. What would you do?”

“Write a message.”

“Exactly. You would like to tell people how you died. No use writing on paper. That would be seen. If you wrote on the wall someone might rest upon it. Now, look here! Just above the skirting is scribbled with a purple indelible pencil: ‘We we–‘ That’s all.”

“What do you make of that?”

“Well, it’s only a foot above the ground. The poor devil was on the floor dying when he wrote it. He lost his senses before he could finish.”

“He was writing, ‘We were murdered.'”

“That’s how I read it. If you find an indelible pencil on the body–”

“We’ll look out for it, you may be sure. But those securities? Clearly there was no robbery at all. And yet he did possess those bonds. We verified that.”

“You may be sure he has them hidden in a safe place. When the whole elopement had passed into history, he would suddenly discover them and announce that the guilty couple had relented and sent back the plunder or had dropped it on the way.”

“You certainly seem to have met every difficulty,” said the inspector. “Of course, he was bound to call us in, but why he should have gone to you I can’t understand.”

“Pure swank!” Holmes answered. “He felt so clever and so sure of himself that he imagined no one could touch him. He could say to any suspicious neighbour, ‘Look at the steps I have taken. I have consulted not only the police but even Sherlock Holmes.'”

The inspector laughed.

“We must forgive you your ‘even,’ Mr. Holmes,” said he “it’s as workmanlike a job as I can remember.”

A couple of days later my friend tossed across to me a copy of the bi-weekly North Surrey Observer. Under a series of flaming headlines, which began with “The Haven Horror” and ended with “Brilliant Police Investigation,” there was a packed column of print which gave the first consecutive account of the affair. The concluding paragraph is typical of the whole. It ran thus:

The remarkable acumen by which Inspector MacKinnon deduced from the smell of paint that some other smell, that of gas, for example, might be concealed; the bold deduction that the strong-room might also be the death-chamber, and the subsequent inquiry which led to the discovery of the bodies in a disused well, cleverly concealed by a dogkennel, should live in the history of crime as a standing example of the intelligence of our professional detectives.

“Well, well, MacKinnon is a good fellow,” said Holmes with a tolerant smile. “You can file it in our archives, Watson. Some day the true story may be told.”